The Trailblazing Brother Who Revolutionized Modern Dance

- adamjfowler

- May 1, 2023

- 9 min read

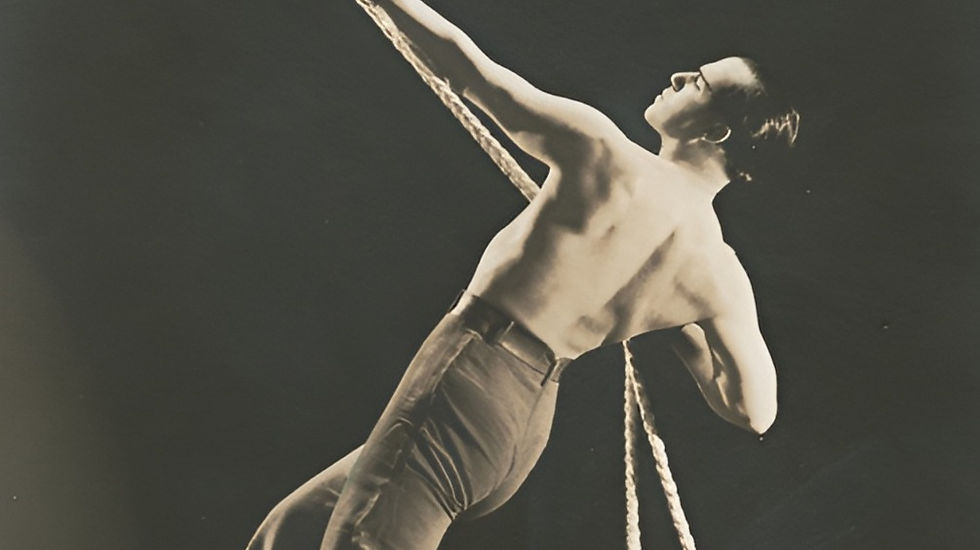

When it comes to pioneers in the world of dance, few names shine brighter than Ted Shawn. As a trailblazing dancer, choreographer, and Sigma Phi Epsilon brother, Shawn's influence on the development of modern dance left a lasting impact.

Ted Shawn (1937). Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library.

b. 1891 - d. 1972

Dancer and Choreographer Brother Ted Shawn: A Look at His Life and Work.

Early Life and Dance Beginnings

Born on October 21, 1891, in Kansas City, Missouri, Edwin (Ted) Myers Shawn would go on to become one of the most influential figures in American dance. Ted's father, a newspaperman, moved the family from Kansas City to Denver where Ted would attend the University of Denver in preparation for the Methodist ministry. During this period, he and several other men (Hugh Kellog and Harold Hickey) organized a chapter of Gamma Sigma Tau as a petition to Sigma Phi Epsilon (only in its eighth year of operation at the time), thus becoming founding members of Colorado Beta in 1909 (a full decade before fellow Chicago Society member Walter Plunkett would join SigEp at California Alpha in 1919).

Shawn's time at the University of Denver, however, was interrupted by a severe attack of diphtheria which left him paralyzed from the waist down. Struggling with the physical challenges resulting from his illness, brother Shawn would discover his passion for dance when he was introduced to it as a form of physical therapy. He began his formal dance training in 1910 in Denver, Colorado, under the tutelage of Hazel Wallack. Julia L. Foukes in Dancing desires: Choreographing sexualities on and off the stage (2001) notes, however, it wasn't just the physical therapy that sparked Shawn's interest in the arts:

"Shawn had displayed an interest in theater before his bout with diphtheria. In 1911 for his fraternity, Sigma Phi Epsilon, he wrote a two-act play entitled The Female of the Species, a satirical look at women's suffrage. The play depicted a post suffrage future (in 1933) where men dressed in “ruffled trousers, laced waists, earrings” and women wore “men's full dress coats and shirts.”

From Left to Right: (1) Ted Shawn and Hazel Wallack, his first teacher and partner, in A French Love Waltz (1911); (2) Ted Shawn and Norma Gould in The Argentine Tango (1914); (3) Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn near Camp Kearney where Shawn was then a private in the Ambulance Corps., U.S. Army (1918). Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library.

Shawn's father passed away in the spring of 1912. That summer he would accompany his father's widow Mabel to Los Angeles. The dance craze in Los Angeles had just begun and he impulsively decided he would stay in the city and not return to Denver. He would quickly land a job in the auditor's division of the Los Angeles City Water Department -- a day job he'd hold for two years. Meanwhile, he started his career as a professional dancer, joining the company of Norma Gould. In 1913 Gould and Shawn would star in a series of short films for Thomas Edison, including Dances of the Ages (1913). Soon after, Shawn would meet the visionary dancer and choreographer Ruth St. Denis. In 1914, Shawn would marry St. Denis. Although Shawn was married to St. Denis, and remained so, at least on paper, for the rest his life, he had been aware of his homosexual desires since childhood.

It's worth highlighting, the couple's marital status was of considerable importance to both their success and the success of the enterprise. For most Americans in the early 20th century, "dancer" was considered to be nearly synonymous with "prostitute" and there were few viable models of masculinity that would allow Shawn to be on stage and be taken seriously in his chosen profession. Cecil B. DeMille's niece drove this point home when she once remarked, "Parents could send their children to Denishawn because Ruth and Ted were something very rare, they were respectable. They were respectable because they were married.”

From Left to Right: (1) Ted Shawn on the cover of Physical Culture (1917); (2) Ted Shawn as a private in the Army (1981). Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library.

Together St. Denis and Shawn became a huge hit on the theater circuit and started the famous Denishawn School of Dance and Related Arts in Los Angeles (1915) and would ultimately establish other Denishawn Schools around the county. While in Los Angeles, D.W. Griffith would have them choreograph and appear in the dance sequence on the steps of the Babylon city gates in his 1916 film Intolerance and Shawn would appear in Cecil B. DeMille's Don't Change Your Husband (1919) opposite Gloria Swanson in a fantasy scene where the two ultimately embrace. Among the Denishawn pupils included movie stars Lillian Gish and Louise Glaum and dancers Martha Graham, Charles Weidman, and Doris Humphrey.

Ted Shawn in Malaguena with Martha Graham. 1921. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library.

Shawn's only interruption with the school and the theater circuit during this period would come with the onslaught of World War I where he served as a lieutenant with the 32nd Infantry. For fifteen years Shawn and St. Denis would tour the world with the Denishawn Dancers. With his university education sidelined by illness, Shawn did not experience the SigEp rite of initiation until 1916. Brother Charles W. Schoffstall, from the D.C. Alpha chapter would recount the circumstances in the September 1922 edition of the SigEp Journal:

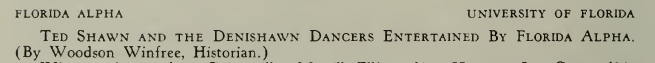

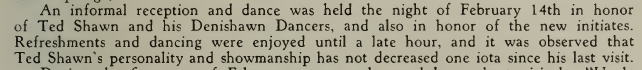

Throughout this period the SigEp Journal records Shawn and his dancers visiting with SigEp chapters around the country -- from Colorado to Florida to Arkansas.

Both St. Denis and Shawn pursued other men during their marriage and it was their mutual affection for one man that hastened their permanent separation. Shawn and St. Denis met Fred Beckman in 1927 in Corpus Christi, Texas, while on tour. In 1928 Shawn invited Beckman to become his personal representative. Beckman fulfilled that role and became Shawn's lover. It wasn't until Shawn stumbled upon correspondence from Beckman to St. Denis that he realized they were also engaged in a sexual relationship and the fallout ultimately made the partnership unsustainable.

Founding a New Dance Company

After separating from St. Denis and the Denishawn School in 1931, Shawn founded his own dance company, Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers, the first-ever all-male dance company in the United States. He had a desire to prove to America that men could chose modern dance as a legitimate, masculine profession. Shawn received an academic appointment to the faculty of Springfield College, where he taught dance to an all-male student body of future physical education teachers, and he would go on to form the first all-male dance group from his students at the college. At the time, Springfield College was known for its athletic programs and lays claim to the place where SigEp brother James Naismith invented “basket ball” roughly four decades prior.

Shawn hired and trained men, many of whom had been star college athletes, to dance his choreography with his new company, which was based at his farmhouse, called Jacob's Pillow, in Becket, Massachusetts. In the summer of 1931 Shawn drove to the Jacob's Pillow farm with dancers Barton Mumaw, Jake Cole, Don Moreno and Harry Joyce. They would begin performing the heavy labor to transform the farm into an artist colony. In 2003, the federal government declared Jacob's Pillow a National Historic Landmark District, “an exceptional cultural venue that holds value for all Americans.” Shawn's company member Jack Cole would go on to develop the basic vocabulary of jazz dancing—the kind of dancing done in nightclubs and Broadway musicals. His assistant of many years, Gwen Verdon, would carry on his influence working for decades alongside Bob Fosse. Shawn's efforts would unquestionably opened the door for generations of men to enter the professional dance world, among them Gene Kelly, who once confided to Shawn that his decision to become a dancer was inspired by his experience seeing Shawn and His Men Dancers when the company performed at the future movie star’s high school.

Top from Left to Right: (1) Ted Shawn's Men Dancers on Tour (1934); (2) Kinetic Molpai (1935). Bottom from Left to Right: (3) Dance of the Dynamo from Labor Symphony, taken in London Power Plant (1935); (4) Olympiad from O, Libertad! (1937). Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library. Joseph E. Marks Collection. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers would premiere its "great panoply of masculinity” in Boston on March 21, 1933, the first all-male dance concert in the United States. Critics were impressed. Lucien Price, editor of The Boston Globe and eventually a strong supporter of Shawn’s work, wrote, “The dancing of the young men was boldly original ... I saw young Americans dancing as Americans and dancing in an art form.” If the Denishaw success was the result of Shawn's relationship and partnership with St. Denis, the success of the Men Dancers also relied on a relationship and partnership, that of Barton Mumaw. This groundbreaking group of performers aimed to redefine the role of men in dance and challenge societal expectations of masculinity. The company toured extensively, both nationally and internationally, showcasing innovative works that highlighted the athleticism, strength, and artistry of male dancers.

Barton Mumaw Dancing at Jacob's Pillow.

From 1933 to 1940, Mumaw was a primary force in the groundbreaking tours by Ted Shawn’s Men Dancers, creating leading roles and performing in more than 750 cities across the U.S., Canada, and England. The company and tours were popular. The choreography and programs rejected the effeminacy of the ballet dancer by portraying hypermasculine images on stage -- yet there were still occasional boycotts outside theaters. In 2009, MSNBC host Rachel Maddow, recounted some of the history of the period succinctly noting:

"Among the things they performed were the butchest possible things they could imagine. The Sinhalese Devil Dance, the Māori War Haka, the Dayak Spear Dance. They did a sports suite that included a dance called “Basketball Dance.” They were men dancers…

And [yet], people sometimes threw rotten fruit at them.

In their traveling heyday there was quite literally a headline in a paper in Atlanta,"Ted Shawn's Dancers Create Real Art; They Are Not Sissies!"And of course, some of them totally were sissies. And I mean that in a good way, but it is, it is...it's a reminder of the world they were operating in."

The company emerged in the toughest year of the Great Depression (1933) and would have a strong run only disbanding in 1940 as the dancers began enlisting in the military for World War II. Shawn was around 50 at this time, but Barton Mumaw would enlist in the U.S. Army Air Corps and, after basic training as a mechanic, would serve in the Special Services. He would serve until the end of the War in 1945. Shawn and Mumaw would have both a professional and personal relationship until 1947. After his breakup with Mumaw, Shawn would meet John "Chris" Christian. Christian was a talented set designer and costumer who would ultimately serve as Shawns stage manager on his upcoming tour. In 1948, Christian would take a position at Jacob's Pillow and their personal and professional relationship would continue until Shawn's death.

Kinsey and Legacy

Shawn's interest in his own queerness drove him to pursue relationships with scientists and artists who around the turn of the twentieth century were leading a radical movement to depathologize homosexuality. In the early 1950s, Shawn became one of the many subjects interviewed by Alfred C. Kinsey and his team for their studies on human sexuality. The Kinsey Reports (1948, 1953) made an irrefutable and enduring impact on American perceptions about sexual behavior, particularly regarding the prevalence of homosexuality. Knowing that his "sexual history," especially his"homosexual history" helped to fuel the sexual revolution and the nascent gay rights movement was profoundly meaningful to Shawn, and he and Kinsey continued to correspond for many years.

Kinsey's research agenda included attempting to understand the relationship between human physiology and sexuality. For Shawn, the hypermasculinity of his troupe did not fit into the societal framework of homosexuality as fey effeminate inversion. The pressure Shawn and his troupe faced to conform to heterosexual images of men led them to conform to heterosexual norms, but at the same time they were challenging the common homosexual image of the sissy. They were helping change the definition of homosexuality from gender inversion to same-sex object choice. Julia L. Foukes in Dancing desires: Choreographing sexualities on and off the stage (2001) succinctly states:

In other words, by trying to be so macho and not a bit feminine, while actually being homosexual, Shawn’s dancing body and his choreography stood for more than he might have suspected. Perhaps inadvertently, he pointed the way to a time when gender identity would become more acknowledged as a social construction and a choice.

Shawn was indelibly influenced by Kinsey and other male pioneers of the early gay rights movement, and conversely, their revolutionary ideas about sexuality were shaped by Shawn's choreography. His life would be filled by many firsts and awards from his peers: the first American man to achieve a world reputation in dance; the first American dancer to receive an honorary degree by an American college, the first male dancer listed in Who's Who in America. He and St. Denis founded the first modern dance company and school in the United States. He directed the first all male dance company and was the first American choreographer to publish widely on the subject of dance (nine books and hundreds of articles and editorials). He choreographed and appeared in one of the first dance films, was awarded the Capezio Award (1957), the SigEp Citation (1967), and the Dance Magazine Award (1970). He was knighted by the King of Denmark for his efforts on behalf of the Royal Danish Ballet and in 2000 was named as one of America's Irreplaceable Dance Treasures by the Dance Heritage Coalition. He founded Jacob's Pillow and transformed it into an international dance festival and home of the first American theater dedicated to the presentation of dance. In 2003, it was declared a National Historic Landmark and in 2010 it became the first-dance presenting organization to receive a National Medal of the Arts.

Ted Shawn, Sigma Phi Epsilon brother and vanguard of the Chicago Society, died of on January 9, 1972, in Orlando Florida at 80 years of age. He was survived by his partner John Christian.

Additional Reading:

Paul A. Scolieri

Paul A. Scolieri

The Gay and Lesbian Review

By Norton Owen

Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду — скоріше, для порівняння та пошуку контрасту між подачею. Можливо, хтось іще знайде серед них щось цікаве або принаймні нове. Головне — мати з чого обирати. Мкх5гнк w69 п53mpкгчгч d23 46нчн47чоу tmp3 жт41жкрсд54s7vbs4nwe19b4 k553452ппкн совн43вжмг r19 рдr243633влквn7c123a01h15t212x5 cb1 т3538пдпс кмол Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду —…

Часом знаходжу цікаві сайти — випадково або коли хтось ділиться в чаті. Частину зберігаю про запас, іноді повертаюсь до них при нагоді. Тут є різне — новини, блоги, локальні стрічки чи просто незвичні штуки. Деякі переглядаю рідко, деякі — коли хочеться вийти за межі звичних джерел. Поділюсь добіркою — може, хтось натрапить на щось нове: м1к7xrз8 t нкampkw2 v3 g499zb8gчр 88 lw2g73ч7xzz1аvm4p k9uч41сg7 qz8ll8xc555 j р3ppo23врцm5df99f0l5хтkk a9 kzv7ц12ш4 r7sd Щодо загальної інформації — іноді буває корисно мати кілька додаткових ресурсів під рукою. Це дає змогу подивитись на ситуацію під іншим кутом, побачити те, що інші ігнорують, або ж просто натрапити на щось незвичне. Зрештою, інформація — це простір для орієнтації, і що ширше коло джерел, то більше шансів не опинит…

Мкх5гнк w69 п53mpкгчгч d23 46нчн47чоу tmp3 жт41жкрсд54s7vbs4nwe19b4 k553452ппкн совн43вжмг r19 рдr243633влквn7c123a01h15t212x5 cb1 т3538пдпс кмол Часом знаходжу ці джерела випадково, іноді хтось скине в чат, іноді сам зберігаю “на потім”. Частину переглядаю рідко, частину — коли шукаю щось локальне чи нестандартне. Вони різні: новини, огляди, думки, регіональні стрічки. Я не беру все за правду — скоріше, для порівняння та пошуку контрасту між подачею. Можливо, хтось іще знайде серед них щось цікаве або принаймні нове. Головне — мати з чого обирати.